Scientists: Stem Cells Colonies Created Without Harming Embryos

By Rick Weiss, Washington Post

Thursday, January 10, 2008; 12:16 PM

Scientists in Massachusetts said today they had created several colonies of human embryonic stem cells without harming the embryos from which they were derived, the latest in a series of recent advances that could speed development of stem cell-based treatments for a variety of diseases.

In June, scientists in Japan and Wisconsin said they had made cells very similar to embryonic stem cells from adult skin cells, without involving embryos. But that technique so far requires the use of gene-altered viruses that contaminate the cells and limit their biomedical potential.

By contrast, the new work shows for the first time that healthy, normal embryonic stem cells can be cultivated directly from embryos without destroying them.

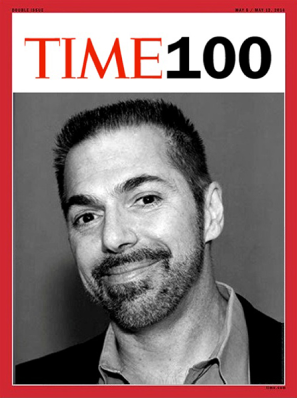

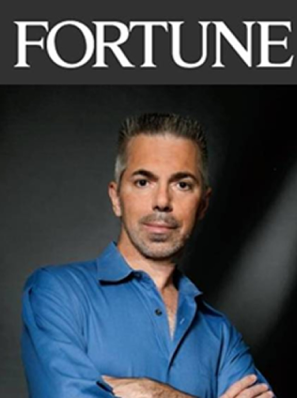

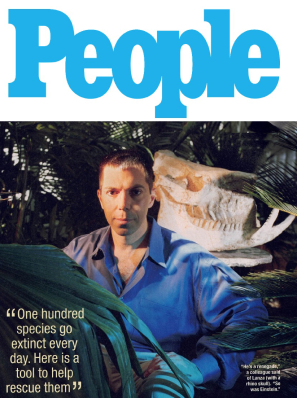

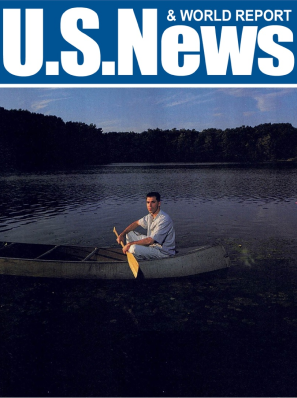

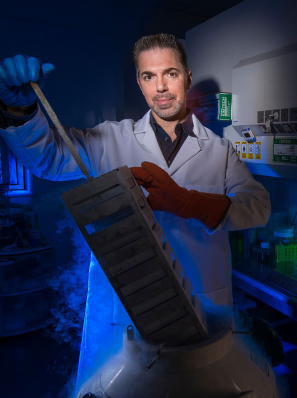

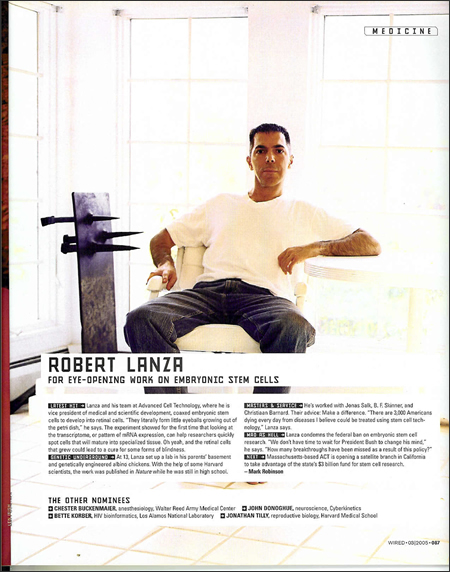

That means the work should be eligible for federal financing under President Bush’s six-year-old policy of funding only stem cell research that does not harm embryos, said study leader Robert Lanza, chief scientific officer at Advanced Cell Technology in Worcester.

But that is not likely, said Story Landis, who heads the National Institutes of Health stem cell task force, which oversees grants for studies on the medically promising cells.

The embryos Lanza used, which were donated for research, appear not to have been damaged, Landis acknowledged. However, she said, “it is impossible to know definitively” that the embryos were not in some subtle way harmed by the experiment.

And “no harm” is the basis of the Bush policy, she said.

Landis said the only way to prove that the technique does not harm embryos would be to transfer many of them to women’s wombs and see if the resulting babies were normal. But it would be unethical to do that experiment, she said, so the question cannot be answered.

That standard has Lanza fuming. By all scientifically recognized measures, he said, the embryos — currently frozen in suspended animation because they were donated for research and not to make babies — are normal, he said.

“I think the burden of proof lies with the NIH and the Bush administration to show that an embryo was harmed,” Lanza said.

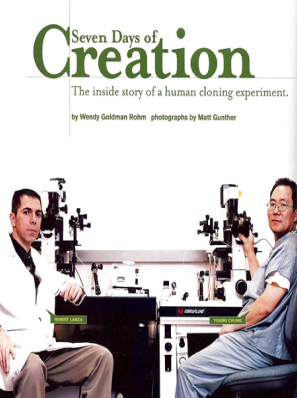

The new technique involves the careful removal of a single cell from a newly formed eight-cell embryo and coaxing that cell to divide repeatedly until it forms a self-replenishing colony of embryonic stem cells.

Fertility doctors perform such “single-cell biopsies” thousands of times every year to test the genetic health of embryos conceived by in vitro fertilization, with little or no apparent effect on the remaining seven cells’ ability to form a normal baby. The idea is to check the removed cell for DNA defects and transfer to the woman’s womb only embryos whose cells test normal.

Lanza’s team first reported growing stem cells from individual embryo cells in 2006. But that work was criticized for not showing plainly that the plucked embryos could develop normally, relying instead on evidence from the nation’s many fertility clinics that embryos can survive the process.

In the new experiments, he and his colleagues allowed their seven-cell embryos to continue growing in laboratory dishes for up to five days — the oldest that embryos are typically cultured in fertility clinic labs before being transferred to a mother’s uterus.

Of 43 embryos biopsied, 36 (or 83 percent) developed into healthy five-day-old embryos, as determined by various measures used by the clinics, the team reports in today’s online edition of the journal Cell Stem Cell.

That’s a survival rate as good as or better than occurs with fertility clinic embryos generally, whether they are biopsied or not, according to several published reports.

“The biopsy had no effect on the embryos’ development,” Lanza said, adding that the effort produced five new colonies of stem cells. That is a much higher efficiency than was previously achieved. And because of improved culture conditions, the new stem cells do not need to be fed chemicals from destroyed embryos, as was previously the case.

“It is a technically impressive piece of work,” said Douglas A. Melton of the Harvard Stem Cell Institute. “They’ve demonstrated their ability to isolate human embryonic stem cell lines without destruction of the embryos” — something few scientists thought possible just a few years ago.

“But the fundamental ethical issue remains,” said Kathy Hudson, director of the Genetics and Public Policy Center at Johns Hopkins University — namely, how to prove that the approach is inherently harmless.

Very few studies have looked at the outcomes of fertility treatments in which biopsies had been performed, Hudson said. And those that have been done — including a widely publicized July report that found that fertility clinic clients who had their embryos biopsied had about a 30 percent lower chance of giving birth — are riddled with flaws, she said.

But one thing is clear, Hudson said: “Embryo biopsy is tricky and requires extraordinary good hands and technical skills. And even in the best hands, embryos are sometimes lost.”

As long as that risk is there, funding under Bush’s policy will not be available, Landis said — with one possible exception.

Although NIH will not fund Lanza’s method of making stem cells, she said, the agency might fund studies on the cells themselves once they are isolated from the embryos with private money and the embryos are shown to be healthy.

Asked who would make that funding decision, Landis said it would be up to NIH officials. But pressed to say whether the White House would have an influence, she paused.

“I’m sure they would have an interest in such a decision,” she said.

Note: This article in its original format can be viewed here.

To download this article as a PDF, please click here.