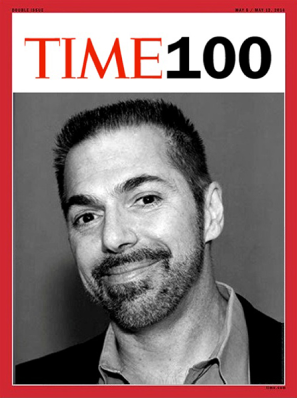

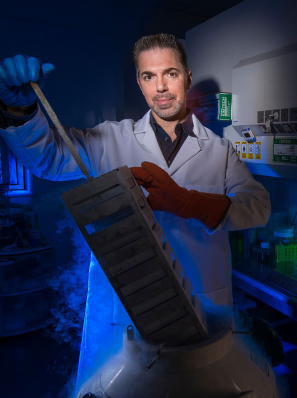

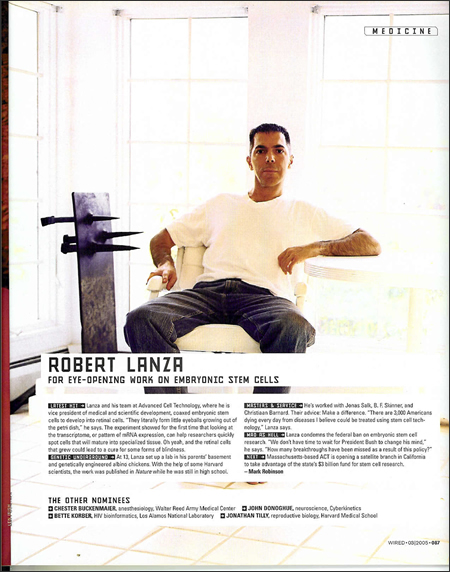

“This is the first time an embryonic stem cell therapy has been approved in Europe,” said Lanza.

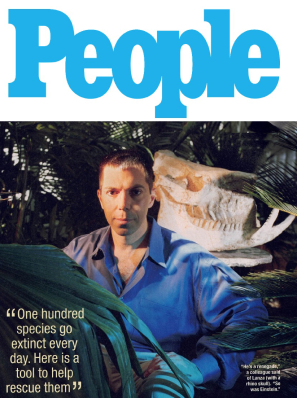

Retinal cells derived from embryonic stem cells will be injected behind patients’ retinas.

Photograph: Roger Tooth/Guardian

British surgeons are to take part in the first trial in patients of a human embryonic stem cell therapy to gain approval from regulators in Europe.

Surgeons at Moorfields Eye Hospital in London will inject cells into the eyes of 12 patients with an incurable eye disease called Stargardt’s macular dystrophy, one of the main causes of blindness in young people. The clinical trial, designed to investigate the safety and tolerance of the groundbreaking therapy, is due to begin in December having received approval from the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency on Thursday. It is the first trial in people of a stem cell therapy to receive the go ahead from regulators in any European country.

Medical teams hope to slow, halt or even reverse the effects of the disease by injecting healthy retinal cells into the eye. The trial is controversial because the replacement retinal cells – known as RPE, or retinal pigment epithelial cells – are derived from human embryonic stem cells.

The Massachusetts-based company Advanced Cell Technology (ACT) announced the trial on Thursday. It will run alongside a similar study that began in July at the Jules Stein Eye Institute at the University of California, Los Angeles. Only one patient has been treated so far in the US trial for Stargardt’s disease. The results from both studies are expected next year.

Patients taking part in the UK trial will have between 50,000 and 200,000 cells injected behind the retina through a fine needle in an outpatient operation expected to take up to an hour. Only patients with advanced disease will be admitted to the trial.

Stargardt’s disease is an inherited disorder that causes progressive vision loss through the thinning of retinal pigment epithelial cells at the centre of the retina, the region where the eye forms its sharpest images. The loss of RPE cells usually begins between the ages of 10 and 20 years and leads to light-sensitive rods and cones in the eye dying off. This ultimately causes vision loss and even blindness.

If the treatment works, the replacement RPE cells will grow and eventually restore the retina to a healthy state that can support light-sensitive cells required for sight.

“This is a safety and tolerability study, so we are dealing with patients with advanced stage disease. Where we expect to get the most significant results is in earlier patients, before they have lost their photoreceptors. We’re hoping to prevent the onset of blindness altogether in those patients,” Robert Lanza, ACT’s chief scientific officer, told the Guardian.

“The UK has been at the forefront of stem cell research in the past, but I think this confirms it is the leader in stem cell work in Europe. This is the first time an embryonic stem cell therapy has been approved in Europe,” Lanza added.

“There is real potential that people with blinding disorders of the retina, including Stargardt disease and age-related macular degeneration, might benefit in the future from transplantation of retinal cells,” said retinal surgeon James Bainbridge at Moorfields and the UCL Institute of Ophthalmology. “The ability to regenerate retinal cells from stem cells in the laboratory has been a significant advance and the opportunity to help translate such technology into new treatments for patients is hugely exciting. Testing the safety of retinal cell transplantation in this clinical trial will be an important step towards achieving this aim,” he said.

Last year, the US company Geron began a long-awaited trial of a stem-cell therapy to repair spinal cord injuries. Doctors hope that injecting stem cells directly into the spine will repair damaged nerve cells enough for paralysed people to regain some movement.